Developing a Curriculum for Low Literate Beginner English as a Second Language Students

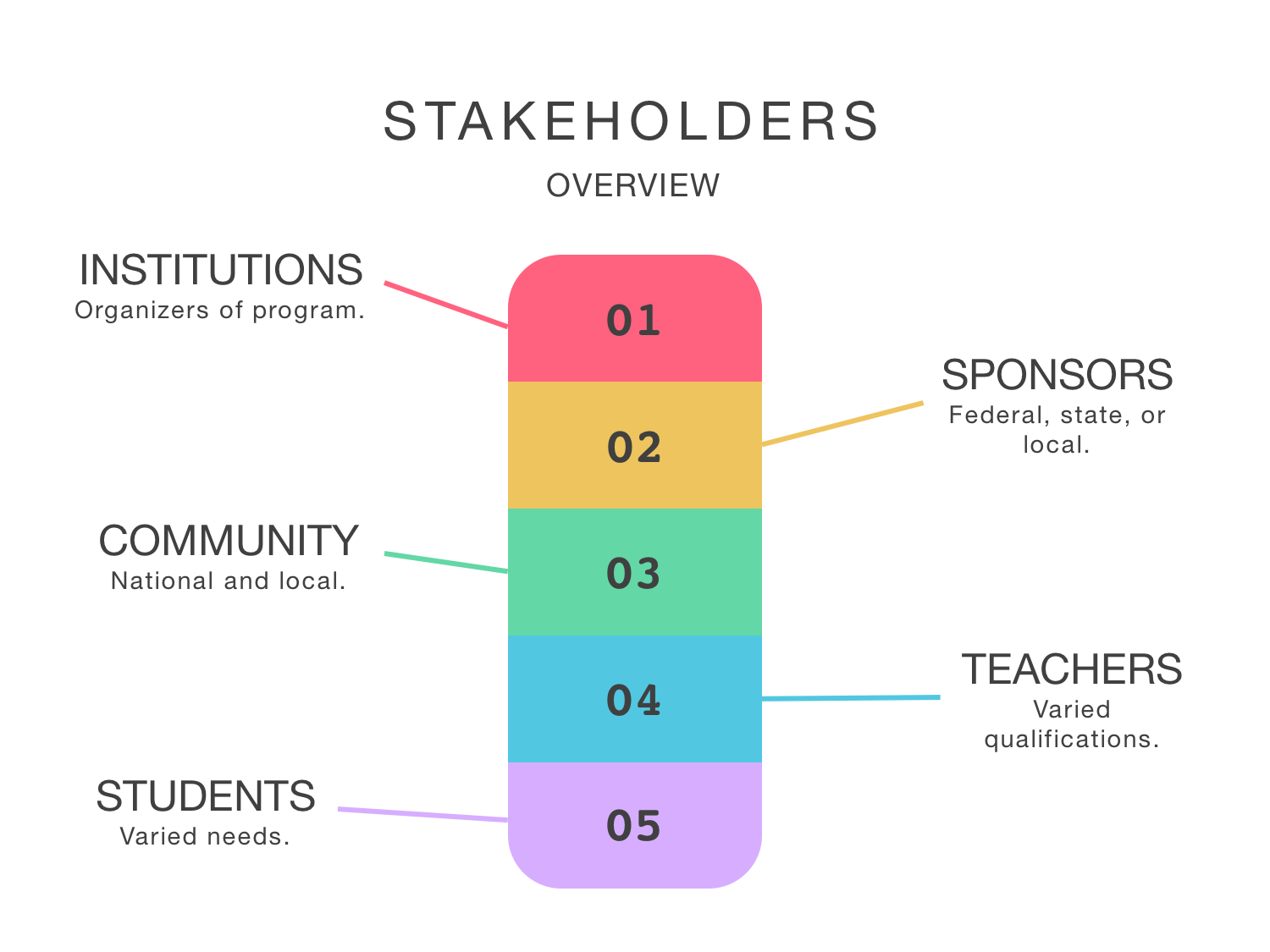

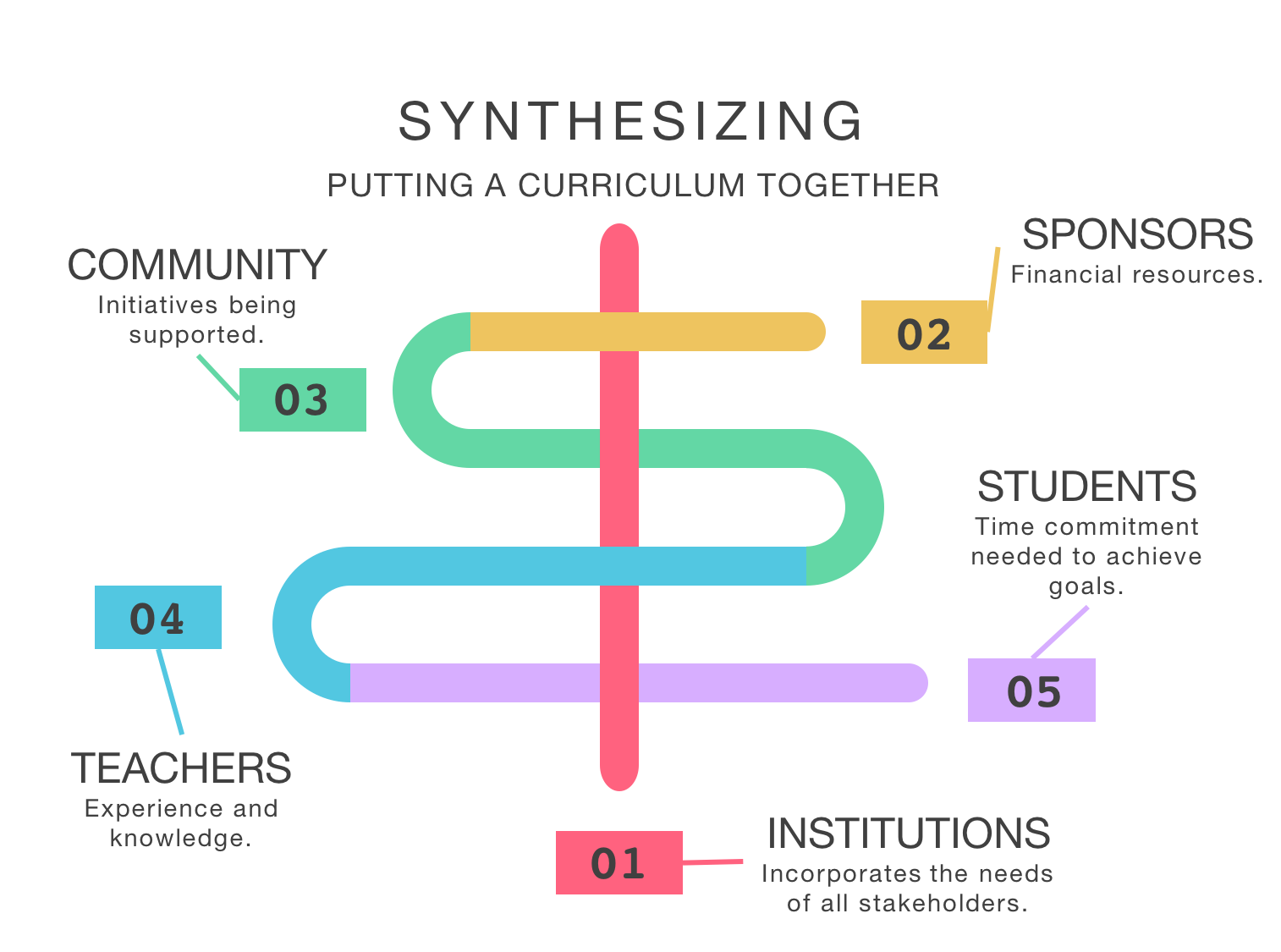

New products or services are designed when there is a gap in the market. However, just because there is a need and demand for certain services does not mean they will be met, especially if they are not lucrative. Take English programs that teach English as a second or foreign language for example. Private programs that are funded by the learners themselves are far spread all throughout the world and can attract qualified professionals to work with them because they are well funded by their own clients. However, many public programs funded through government initiatives have considerably less funding and serve less privileged populations who cannot afford to pay for private classes. Unfortunately, their situations make them the population who is most in need of educational services, which are becoming privatized. Additionally, trends in teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) focus more on the training and hiring of teachers to cater more towards the populations that will pay their salaries, or privatized English programs. However, there is a substantial number of underserved learners who have specific learning needs. This research aims to breakdown and educate TESOL professionals on the key aspects that must be considered when implementing a program for underserved English language learners who need not just English language skills but also basic literacy skills. The following will reflect on the research of the students’, institutions’, and instructors’ needs when implementing a literacy program for students who have a zero-beginning level of English. These needs will then be considered in addition to further research for choosing appropriate material for the course and organization.

Adult English language learners’ needs analysis

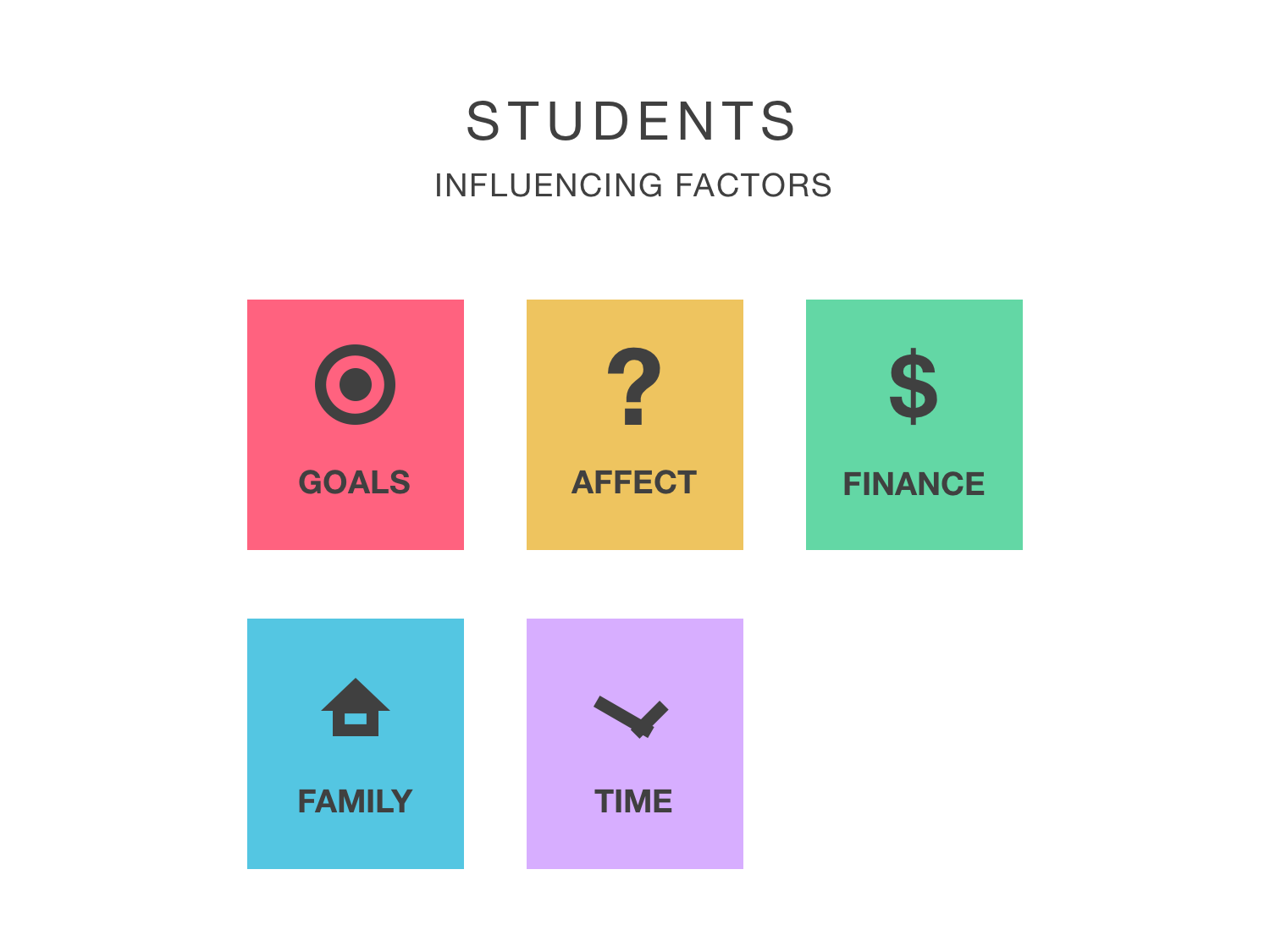

The 2000 census revealed that 35 million residents of the United States of America were non-native English “speaking adults of which 9 million do not speak English well” (Burt, Payton, Adams, 2003, p 8). 2002 statistics show that 42% of adults that took federal funded adult education classes were enrolled in English as a second language (ESL) classes (Burt, Payton, Adams, 2003, p 8). These statistics illustrate the need adult English language learners (ELLs) have for language classes. Those taking English classes may be struggling with reading and writing in general and not just with the language. According to Henneberg (1986), research done on preliterate education for adults found that literacy programs only reach 4% of the illiterate population. Reaching the target population is not as easy as offering more classes. One reason being that those in need of literacy programs tend to be living below the poverty level (Hayes, 1989, p 48). Therefore, attending classes may not be plausible if they need to pay for child care, transportation, or class fees. Besides these financial obstacles, the applicability of their gained knowledge has a huge impact on student participation.

Literacy classes need to outline clearly what a student can expect to realistically achieve by the end of the session or term. To do this, curriculum developers must consider the range of goals potential students have. Previous research has shown the outcomes for literacy programs do not meet students’ goals. Condelli & Wrigley (2008) compared students’ levels before and after participating in a literacy program and found that reading levels increased from the 1.5 grade level to just the second grade, yet oral English levels improved dramatically over the period of study (p 143). Malicky and Norman (1994) found that students who participated in literacy programs were left unsatisfied because they tended to continue working in similar positions they had been working in before the program (p 126). These students’ goals to improve professionally were not met. This same study found that functional literacy skills have rarely led to significant improvements to “employment, personal and economic growth, job advancement, or social integration” (Malicky & Norman, 1994, p 126). Teachers and program designers must take this information into account when providing courses to students. The curriculum and material should enable students to grow personally and professionally, which in turn should influence other goals. Therefore, further skills need to be incorporated into literacy programs. For example, in addition to functional literacy, a program could also help build professional skills to help increase employment opportunities. Ideally, different types of classes could be offered, each with its own specific goals. These goals can then be used to publicize the course to attract students with similar needs. Regrettably, space, budgets, and class size constraints often limit this possibility (Perry & Hart, 2012, p. 111). This results in a variety of student expectations in a single class, and more work and creativity on the part of the teacher. What students learn and how they practice and apply their language skills in class need to be applicable to their goals outside of the classroom.

The relevance of lessons and materials is necessary to meet students’ goals. Learners should see how the materials can be used outside of class. Consequently, starting with lower level materials may be frustrating to students, but working with materials that are beyond their level is equally wearisome. However, Henneberg (1986) is one who avoids using the fabricated language of textbooks and uses real materials with pre-literacy students: “newspapers and magazines, government forms, novels, direct mail advertisements, bank statements, and poetry” (p 55). Because learners participate in these programs to learn how to manage and work with real written texts, students learn better when they are using real materials they may interact with outside of the class (Burt, Peyton, & Adams, 2003, p 22). Luckily, as Henneberg (1986) demonstrates, real materials can be used and applied to lower levels through scaffolding techniques such as altering tasks rather than the materials. A teacher should choose materials that reflect students’ goals and intended uses for literacy. If students use fabricated, watered-down resources, this could be disheartening to students because they will never see this kind of material anywhere but class. Burt, Peyton, and Adams (2003) list a few general uses of functional literacy that may influence the materials a teacher chooses for class: increased job success, involvement in their kids’ education, participation in the community, continuing education, or gaining US citizenship (p 21). These are some common reasons students may want to increase their literacy skills, yet the possibilities are endless. Besides meeting students’ needs, the fact that they have not received literary instruction has to be analyzed and understood to optimize the learning environment.

Students’ backgrounds and experiences can inform the instructor about students’ attitudes and reactions to different components of a course. Being aware of past student experiences can facilitate teaching and learning. Hayes (1989) illustrates how a limited understanding of the different factors that influence specifically Hispanic adult participation in English literacy courses can result in unsuccessful programs (p 48). After conducting surveys on factors that influence students’ participation, Hayes (1989) clustered the students into different groups (see table 1 in Appendix). “This cluster analysis helps understand distinctions among individuals who might appear similar if described according to only one or two characteristics” (Hayes, 1989, p 60). This shows that although an instructor may have a general impression of the factors impacting a general group of students, he or she should also take the time to investigate the individual circumstances of each student.

Knowing what factors impact students’ participation can assist teachers and programs in addressing these needs. Hayes (1989) cites a previous study of his and Darkenwald that claims there are five general factors that affect adult participation in literacy classes: “low self-confidence, social disapproval, situational barriers, attitude to classes, and low personal priority” (p 49). The role the teacher can play to influence some of these factors can only take place once the student has taken the biggest step: deciding to come to the class. Students attending a class have somehow overcome or may be struggling to keep at bay various situational barriers they may have encountered. Helping learners overcome situational barriers is a collaborative effort of teachers, administrators, and sponsors of the program. For instance, financial resources permitting, the institution can offer classes at a variety of times, at different locations, and provide child care while students attend class to encourage more participation in ESL programs. As for students’ self-confidence and attitudes to classes, the learning environment the teacher provides can highly influence these factors. Making students comfortable is vital because stressful, intimidating environments may lead to lowered self-esteem and consequentially, the decision to drop out of the program (Alcala, 2000). One way to avoid intimidating students is to build on the students’ knowledge and make them feel empowered and knowledgeable in ways that may not relate to literacy. Developing positive attitudes and building learners’ self-confidence could also help raise the personal priority students put on their classes. However, many adult students must deal with work and family commitments before even considering taking a class. The likelihood of it being or become a student’s number one priority is low, but it could become more important than they had first thought.

Another factor that the program may not have much power to influence is social disapproval which can manifest in a variety of ways according to the context. If the program is offered at the workplace there may be supervisor resistance who may be more concerned with work being finished on time (Pierce, Harper, & Burnaby, 1993, p. 17). When teaching workplace English to the hotel staff in Los Altos, California, my students would occasionally miss classes as well according to their daily workload. The same study found that students may not participate because of coworker resentment, some Anglophone coworkers ask “Why are we doing this for these foreign people” (Pierce, et al., 1993, p. 21). These can be some of the downsides to offering classes during the work schedule. Pierce et al. (1993) found that programs that took place after, instead of during the work day, had higher levels of participation because there was less work related pressure on the students. However, social disapproval can also come from the home. One manager in Pierce, Harper, and Burnaby’s study on workplace English (1993) stated “we have some cases where people are reluctant to take homework home because their husband doesn’t know that they’re going to take it to school” (p. 25). Similarly, at an adult school in Morgan Hill, California, a lead teacher I volunteered with explained the struggles some of the women must go through because their spouses do not want them to attend class. Overcoming social disapproval can be facilitated by understanding and working with the pressures students face from others outside the classroom.

For low literate students, it is important that they feel comfortable, respected, valued, and competent while working on lower level reading and writing skills. To achieve this, low literate students need to have a course specifically for low literacy and not just be placed in the lowest ESL level available (Henneberg, 1986, p. 54). This should be avoided because many literate learners are impatient with students who lack literacy skills (Henneberg, 1986, p. 53). Negative feelings and peer pressure will not facilitate the supportive environment these learners need. Condelli and Wrigley (2008) pre- and post-program reading tests showed a difference in students’ gains in performance based on students initial basic reading skills. “Adult ESL literacy students who entered class with some basic reading skills showed significant growth in reading comprehension compared to students who had little or no basic reading skills” (Condelli & Wrigley, 2008, p. 13).

English language learner adult literacy instructors’ needs analysis

Crandall (1993) describes the context “adult literacy practitioners work” as “large, multilevel classes, [with] limited resources, substandard facilities, intermittent funding, [and] limited contracts with few benefits” (p 497). These classes are given as an afterthought, using facilities that are not specifically for their course. The assumption that if one speaks a language they can teach others the language, and the same goes for reading, explains the reliance on volunteers in this field. However, this reliance on volunteer tutors as instructors poses a challenge to the success of literacy programs.

Relying on volunteer instructors undermines the importance of literacy programs. Unfortunately, this is a reality due to financial constraints. Many programs work with “volunteer educators who may have little (if any) professional experience” (Perry & Hart, 2012). In turn, volunteers are usually trained between 15-20 hours (Crandall, 1993), but trainees still feel unprepared after their training programs (Perry & Hart, 2012). Having gone through a similar adult literacy training for a volunteer adult literacy tutoring position at a local library, I too can shed light on the 14-hour crash course for tutoring low literate adults. The training provides a volunteer tutor with a well-organized binder, a textbook to reference, a diagnostic report about each tutee, and a guide through their office which has a plethora of resource books and materials tutors can access. In addition to resources, the trainings go over different activities one can do with a student and encourage tutors to personalize and make their lessons relevant to the tutee. So, the training and support provided offer enough information to get started. Similarly, some literacy tutors in Perry and Hart’s (2012) study on literacy educators stated that “hands-on experience had been more helpful than training. In contrast, Carrie and Katie felt they had received some benefit from training, including confidence, access to (and knowledge about) resources, and apprenticeship” (p. 117). Trainings can be helpful because they show tutors that they can seek out additional knowledge. However, training does not assure that tutors gain the knowledge needed to become successful facilitators. The logical solution to this would be to offer well-paid positions to adult ESL professionals. However, the current situation deems this impossible.

The current employment situation devalues adult ESL professionals. Crandall (1993) reports that 80-90% of adult literacy instructors do not receive contracts or benefits, nor work full-time. In fact, as stated above, they often work as volunteers. Opportunities may be available to work full time as program administrators but not as instructors. Programs usually try to stretch their funds by employing more part-time instructors or volunteers than employ full-time instructors to avoid paying them costly benefits. This reality demands instructors seek part-time positions at various locations that require distinct skills and knowledge. For example, students at a community college have different needs and expectations than students taking a course at an adult school, so teachers working at two or more locations need to have a wide range of abilities to serve distinct populations well.

Most MA TESOL programs focus on the teaching of forms but do not address literacy needs. ESL literacy instruction includes both language and literacy skills. (Crandall, 1993, p 500) Basic requirements for teaching adult ESL literacy consist of “special knowledge of theory and practice in L1 and L2 literacy, cross-cultural awareness, and the development of skills for teaching ESL literacy to adults in educationally and culturally appropriate ways” (Crandall, 1993, p 501). Those hired as volunteers have degrees in diverse fields, education degrees usually for kids or teens, not adults, and if they do have TESOL backgrounds, they have little preparation for working with adults with limited education. (Faux, 2006, p 138). Even if instructors are well prepared, contexts and students vary greatly. Hence, practitioners should continue to develop through their practice and in-service education to continuing learning and growing.

Choosing resources

Adult literacy instructors can use Individualized Language Development Plans (ILDP) to determine appropriate instructional strategies for preliterate students, which has been done with preliterate children in public schools. According to Alcala (2000), author of the article “The preliterate student: A framework for developing an effective instructional program,” an ILDP should include a) an assessment of the learners’ current academic performance in his/her L1 b) both short-term goals that will lead to successful attainment of long-term goals c) the length of time the learners are to be in the language development program d) who is responsible for which aspects of the linguistic services given e) specific materials and teaching strategies to be used and f) suitable assessment. Adult literacy programs are language development plans, but instead of being individualized like in public schools they aim to target a group of learners. Hence, the factors listed above need to be considered while designing an English literacy curriculum as well.

Students with low literacy skills who have limited ELP are at a disadvantage when trying to learn to read, write, or acquire vocabulary. One must have some vocabulary knowledge to put meaning to words he or she wants to read. Acquiring more vocabulary is also facilitated by being able to read and write. Yet, if one just relies on the spoken use of the word, revisiting the word later is then limited to auditory use. Coady (1997) asks “how can they learn enough words to learn vocabulary through extensive reading when they do not know enough words to read well?” (p. 229). It is obvious that building a vocabulary with limited literacy skills can be a challenge for teachers and learners alike. Laufer (1997) states that the amount of word families that a reader needs to be able to achieve basic reading comprehension is around 3,000, which amounts to approximately 5,000 lexical items (p. 24). However, this lexical threshold applies for “good L1 readers” so learners with limited literacy skills will struggle even more to acquire reading skills in another language (Coady, 1997, p. 239). Coady (1997) offers a solution to enable independent reading by exposing learners to highly frequent words. However, this is not enough to promote literacy skills. Students also need to build their decoding skills simultaneously along with common sight words.

Simplified texts or graded readers have been used with students with less vocabulary knowledge to make texts more comprehensible. Coady (1997) reports the downside of using inauthentic simplified texts because, when they are rewritten, they tend to be stripped of “normal syntactic and pragmatic usage of an ordinary text” (p. 231). Learners need to become familiar with these aspects of the language as well, not just amass vocabulary. Furthermore, simplified materials do not prepare students to interact with the English that is used outside the classroom. On the other hand, beginning level native speakers are not presented with difficult texts when they are learning how to read. If learners are presented with materials that are well beyond their abilities, this can lead to frustration and discouragement. Students are in low literacy classes because learners need more appropriate materials that suit their more basic literary needs as well as less pressure from more advanced students (Henneberg, 1986, p. 54). Therefore, a middle ground may be the best approach: using “simplified materials for beginners, but … the goal must be to move as quickly as possible to more authentic native speaker texts” (Coady, 1997, p. 231). Considering that low level English students should start out with level appropriate texts and should learn to recognize the most frequent words automatically, students still need a foundation of the basic mechanics in reading and writing before they can approach texts.

Connecting literacy teaching to everyday life by working with information students have experience with or want to know more about works better than using materials solely geared towards literacy. This material, of course, should reflect the course goals. If it is geared towards enabling parents to interact with their children’s school, material should be about and from local schools, such as notes from and to teachers, field trip permission slips, or the school’s website or online grade system for example. By using materials that students are interested in “and by creating situations for cognitive involvement, teachers can create interest, maintain high levels of motivation, engage student’s minds and through this process build literacy skills that have importance in the lives of adults” (Condelli & Wrigley, 2008, p. 17). However, when selecting materials, the instructor should not overwhelm the students. A suggestion for using authentic material is to lead up to it, as aforementioned (Coady, 1997), by creating documents similar in nature but with only the key information that students need. After sufficient practice, students can be given samples of actual material they may encounter and can work on identifying the parts they do know.

References

Alcala, A. L. (2000). The Preliterate Student: A Framework for Developing an Effective Instructional Program. ERIC/AE Digest.

Brod, S. (1999). What Non-Readers or Beginning Readers Need to Know: Performance-Based ESL Adult Literacy. Spring Institute for International Studies, Denver, CO.

Burt, M., Peyton, J. K., & Adams, R. (2003). Reading and Adult English Language Learners: A Review of the Research. National Center for ESL Literacy Education (NCLE).

Center for Applied Linguistics. (2010). Education for adult English language learners in the United States: Trends, research, and promising practices. Washington, DC: Author.

Coady, J. (1997). L2 vocabulary acquisition through extensive reading. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition (pp. 225-237). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Condelli, L., Wrigley, H. S. (2008). The what Works study: Instruction, literacy and language learning for adult ESL literacy students. In S. Reder and J. Bynner (Eds.). Tracking adult literacy and numeracy skills: Findings from longitudinal research, 133-159.

Crandall, J. (1993). Professionalism and professionalization of adult ESL literacy. TESOL Quarterly, 27(3), 497-515.

Faux, N. (2006). Preparing teachers to help low-literacy adult ESOL learners. LOT Occasional Series, 6, 135-142.

Gonzalez, A. (2007). California's Commitment to Adult English Learners: Caught Between Funding and Need. Public Policy Institute of CA.

Hayes, E. (1989). Hispanic adults and ESL programs: Barriers to participation. TESOL Quarterly, 23(1), 47-63.

Henneberg, S. (1986). What do you mean, you can’t read? The English Journal, 75(1), 53-55.

Holt, G. M. (1995). Teaching Low-Level Adult ESL Learners. ERIC Digest.

Kaufman, R. S. (1994). State Funding for Community College Noncredit Continuing Education Courses. Digital Library and Archives E Journal, 24(2). Retrieved from https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/CATALYST/V24N2/kaufman.html

Laufer, B. (1997). The lexical plight in second language reading: Words you don’t know, words you think you know, and words you can’t guess. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition (pp. 20-34). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Malicky, G. V., & Norman, C. A. (1994). Participation in adult literacy programs and employment. Journal of Reading, 38(2), 122-127.

Peirce, B. N., Harper, H., & Burnaby, B. (1993). Workplace ESL at Levi Strauss: "dropouts" speak out. TESL Canada Journal, 10(2), 09-30.

Perry, K. H., & Hart, S. J. (2012). “I'm just kind of winging it”: Preparing and supporting educators of adult refugee learners. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(2), 110-122.

Vinogradov, P., & Bigelow, M. (2010). Using Oral Language Skills to Build on the Emerging Literacy of Adult English Learners. CAELA Network Brief. Center for Adult English Language Acquisition. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED540592.pdf

Young, M., Fleischman, H., Fitzgerald, N., & Morgan, M. (1994). National evaluation of adult education programs: Patterns and predictors of client attendance. Arlington, VA: Development Associates.